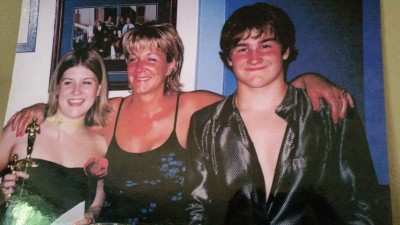

Eighty crosswalks and 45 light-rail stations made safer. That’s how Darla Sturdy sums up her proudest accomplishment to date. Sturdy, a Gresham mother and career bookkeeper, never imagined a second life as a transportation engineer, much less as a lobbyist. But this is the work she threw herself into after her boy was run over and killed by a MAX train.

Families for Safe Streets

On the evening of June 23, 2003, she got a knock on her door from a uniformed stranger asking if Darla was the mother of a boy named Aaron. “There were police there, and Aaron just didn’t get into trouble,” she recalled.

Darla told them yes she was Aaron’s mom and invited them in. One of them pulled out an ID card that showed a younger, hardly recognizable version Aaron, then a 16-year-old student at Gresham High. “It was completely out of date,” Darla remembers. But there was no question it was him.

That night, Darla’d been up waiting for Aaron to return from a church youth group meeting. But as she learned from her visitors — who also included a coroner and a chaplain trained in grief support — he’d been struck and killed in a crosswalk at the MAX station at Gresham City Hall, just five minutes from their house. Aaron was riding his bike westbound next to the MAX tracks and turned left to get across the tracks on the pedestrian crossing. He meant to cross behind an east-bound train that was just pulling out.

However, a second west-bound train was pulling in at about 35 mph and Aaron didn’t spot it until it was too late. The driver honked, but it was too late. Aaron’s bike left a 6-8-foot skid mark, according to the police report.

For months after her son’s death, Darla was in a daze. She lost weight and had to quit her job as general manager of the Spa Outlet. She says her mind just shut down. “I lost who I was. It’s kind of like when you lose a child, you lose you, too. And your family loses you, because you went with him.”

In her grief, she started taking daily drives from her home, to the MAX station, to the cemetery where Aaron buried — trying to make sense of it. At the MAX station, she watched trains coming in and out and saw several close calls with people crossing the tracks. A friend with a radar gun confirmed that incoming speeds were 35 mph. It settled in her mind that the crossings were unsafe — and that this is what killed Aaron. “It took me about three years, but I finally realized why God put me here.”

LOOKING OUT FOR EACH OTHER

Sturdy knew she could never bring back her own boy. But she could help other families avoid a similar fate. Having grown up in the small town of Milton-Freewater, Darla saw it as her duty. “In small towns, people look out for each other,” she said.

TriMet laid the MAX lines in Gresham in the eighties, when the Portland suburb was much less developed. Although a few newer MAX stations on Portland’s west side had gated pedestrian crossings, most didn’t, certainly not the legacy stations in Gresham, and by then Gresham had grown into a bustling suburb with schools, homes, and businesses right next to the tracks.

Sturdy began collecting data on MAX’s safety record, finding 505 crashes (including 108 with pedestrians or cyclists) between 1994 and 2006. She compiled photos of unsafe pedestrian crossings, including one in Gresham that lied just 25 feet from a public school. TriMet’s own internal guidelines called for protective gates for crossings within 600 feet of schools.

Darla took her growing folder of evidence to the Oregon State Capitol and began working there every Wednesday and Friday, meeting 12 to 15 legislators each visit to get support for a bill she dubbed Aaron’s Bridge to Safety. All the while, she pulled full shifts at the Spa Outlet on weekends.

It was no easy fight. After she’d collected the needed signatures in the House, the chairwoman of the transport committee refused to give the bill a hearing. “She was new, and she didn’t want to take on TriMet,” Darla explained. So she introduced the bill in the Senate, and “did it all over.

In 2007, the governor signed Senate Bill 829 into law, requiring TriMet to submit to an independent safety review of nearly 80 of its sidewalks. It took years of more lobbying– and the death of another pedestrian at the same Gresham City Hall crossing — but finally, the study’s recommendations were put into force. TriMet started carrying out the improvements in 2009, and they were at last finished in 2017 — 45 stations and 80 sidewalks made safer thanks to the tireless efforts of an angry mother.

TAKING IT NATIONAL

With that chapter closed, Darla has lately refocused her energy on family. But rail safety remains a huge concern, and Darla says she wants to take it national. In the meantime, she supports the local chapter of Families for Safe Streets and occasionally attends TriMet Board meetings along with another aggrieved parent, David Sale, whose daughter Danielle was hit and killed by a bus in 2010.

Looking back, Darla’s proud of her accomplishments but still struggles with the cost. “If I could go back in time, I’d want to have my son back,” Darla said. “Except for: I believe we have a purpose. God gave me this purpose, even with how hard it’s been.”